Square Peg, Round Hole

I recently gave a small talk to a room of Master’s students about finding their professional “fit”. Halfway through, one of the students raised her hand and bravely shared why, in her mind, she knew wasn’t a fit at her current workplace.

She worked at a software company where she felt like the “odd one out”. She was non-technical, surrounded by technicians. She was extroverted, surrounded by introverts. She was just too different from everyone else she worked with.

This framing stuck with me.

It’s the most natural thing in the world to want to be part of an organization full of “people like us”. We want to feel in sync with the culture. We want to feel like we’re surrounded by our people and that our skills and personality are a natural extension of the team.

But fitting in requires blending in. And blending in is the first step towards disappearing. To be just like everybody else is to never feel different or uncomfortable. But it might also mean never being given the chance to demonstrate your value.

How can we claim to be “special” if we aspire to be like everybody else? When we seek to never stand out, then we can’t be surprised if we never shine.

In a world that craves unique ideas, unique energy, and unique performance — being different gives you the chance to distinguish yourself and offer something no one else can.

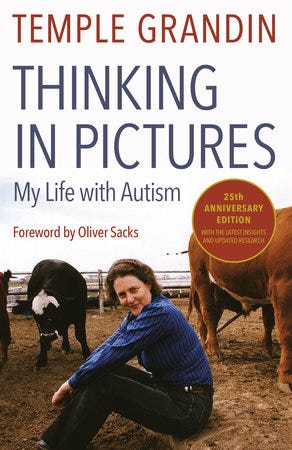

Consider Temple Grandin, an autistic woman who was a pioneer in the animal sciences industry. When she entered this male-dominated field in the 1970s, she didn’t just think differently; her mind processed the world differently. As she puts it, she “thinks in pictures”, a way of thinking that was completely alien to her colleagues.

Where her peers saw a “problem” (her inability to fit in socially, her odd way of thinking through challenges), she possessed a “hidden value” that was invisible to everyone else. That unique viewpoint, born directly from not fitting in, allowed her to be a pioneer in her industry.

We see smaller, everyday versions of this in our own offices.

Some people might seem like “the loner.” They don’t “fit in” with a team’s loud, extroverted, “brainstorm-out-loud” culture. But maybe they’re simply listening. They are processing, synthesizing, and hearing what everyone is actually saying beneath the noise.

Then there’s “the naysayer.” The the person who comes across as negative, cynical, and “not a team player.” In a kickoff meeting where everyone else is optimistic, they’re the one asking, “What if this fails?” or “What’s our fallback plan if we lose our key supplier?” But this person isn’t trying to kill the project; they’re trying to save it. They are providing free, high-level risk management.

Or what about the “the scatterbrain” (my chosen vice). Their desk is a mess, nothing is organized, and they seem incapable of following a simple, linear A-to-B-to-C process. But this non-linear thinking is a superpower. When the rest of the team hits a logical dead end, this is the person who will have the breakthrough, connecting seemingly random ideas to create something entirely new.

The best teams are collections of uniquely singular players; diasporas of individuals with individual skills, talents, and perspectives. Someone is always able to handle the note-taking, someone the analytical work, someone the public speaking.

In the wrong role, each of these people is a liability, but in the right one, they shine.

The work we’ve chosen to do is defined by finding our own individual way to having a meaningful impact. Each of us brings our own unique self to that project. Your gifts differ from my gifts which differ from others gifts. What we seek are opportunities that lean into our gifts, allowing us to shine.

The more we force ourselves into the corporate cookie cutter, the less likely we are to stand out from the crowd.

The extrovert in a room full of introverts isn’t supposed to suppress their natural ability, they’re supposed to find the opportunity to accentuate it.

Good luck out there.

Patrick